Wheatstone bridge

A Wheatstone bridge is an electrical circuit used to measure an unknown electrical resistance by balancing two legs of a bridge circuit, one leg of which includes the unknown component. Its operation is similar to the original potentiometer. It was invented by Samuel Hunter Christie in 1833 and improved and popularized by Sir Charles Wheatstone in 1843. [1]

Contents |

Operation

In the figure,  is the unknown resistance to be measured;

is the unknown resistance to be measured;  ,

,  and

and  are resistors of known resistance and the resistance of

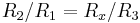

are resistors of known resistance and the resistance of  is adjustable. If the ratio of the two resistances in the known leg

is adjustable. If the ratio of the two resistances in the known leg  is equal to the ratio of the two in the unknown leg

is equal to the ratio of the two in the unknown leg  , then the voltage between the two midpoints (B and D) will be zero and no current will flow through the galvanometer

, then the voltage between the two midpoints (B and D) will be zero and no current will flow through the galvanometer  . If the bridge is unbalanced, the direction of the current indicates whether

. If the bridge is unbalanced, the direction of the current indicates whether  is too high or too low.

is too high or too low.  is varied until there is no current through the galvanometer, which then reads zero.

is varied until there is no current through the galvanometer, which then reads zero.

Detecting zero current with a galvanometer can be done to extremely high accuracy. Therefore, if  ,

,  and

and  are known to high precision, then

are known to high precision, then  can be measured to high precision. Very small changes in

can be measured to high precision. Very small changes in  disrupt the balance and are readily detected.

disrupt the balance and are readily detected.

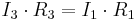

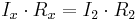

At the point of balance, the ratio of

Therefore,

Alternatively, if  ,

,  , and

, and  are known, but

are known, but  is not adjustable, the voltage difference across or current flow through the meter can be used to calculate the value of

is not adjustable, the voltage difference across or current flow through the meter can be used to calculate the value of  , using Kirchhoff's circuit laws (also known as Kirchhoff's rules). This setup is frequently used in strain gauge and resistance thermometer measurements, as it is usually faster to read a voltage level off a meter than to adjust a resistance to zero the voltage.

, using Kirchhoff's circuit laws (also known as Kirchhoff's rules). This setup is frequently used in strain gauge and resistance thermometer measurements, as it is usually faster to read a voltage level off a meter than to adjust a resistance to zero the voltage.

Derivation

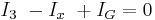

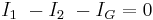

First, Kirchhoff's first rule is used to find the currents in junctions B and D:

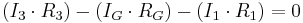

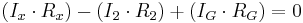

Then, Kirchhoff's second rule is used for finding the voltage in the loops ABD and BCD:

The bridge is balanced and  , so the second set of equations can be rewritten as:

, so the second set of equations can be rewritten as:

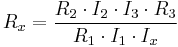

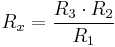

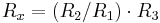

Then, the equations are divided and rearranged, giving:

From the first rule,  and

and  . The desired value of

. The desired value of  is now known to be given as:

is now known to be given as:

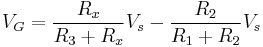

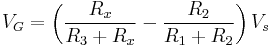

If all four resistor values and the supply voltage ( ) are known, and the resistance of the galvanometer is high enough that

) are known, and the resistance of the galvanometer is high enough that  is negligible, the voltage across the bridge (

is negligible, the voltage across the bridge ( ) can be found by working out the voltage from each potential divider and subtracting one from the other. The equation for this is:

) can be found by working out the voltage from each potential divider and subtracting one from the other. The equation for this is:

This can be simplified to:

where  is the voltage of node B relative to node D.

is the voltage of node B relative to node D.

Significance

The Wheatstone bridge illustrates the concept of a difference measurement, which can be extremely accurate. Variations on the Wheatstone bridge can be used to measure capacitance, inductance, impedance and other quantities, such as the amount of combustible gases in a sample, with an explosimeter. The Kelvin bridge was specially adapted from the Wheatstone bridge for measuring very low resistances. In many cases, the significance of measuring the unknown resistance is related to measuring the impact of some physical phenomenon - such as force, temperature, pressure, etc. - which thereby allows the use of Wheatstone bridge in measuring those elements indirectly.

The concept was extended to alternating current measurements by James Clerk Maxwell in 1865 and further improved by Alan Blumlein in about 1926.

Modifications of the fundamental bridge

The Wheatstone bridge is the fundamental bridge, but there are other modifications that can be made to measure various kinds of resistances when the fundamental Wheatstone bridge is not suitable. Some of the modifications are:

- Carey Foster bridge, for measuring small resistances

- Kelvin Varley Slide

- Kelvin Double bridge

- Maxwell bridge

See also

- Murray loop bridge

- Maxwell bridge

- Wein's bridge, see Wien bridge

- Phantom circuit - a circuit using a balanced bridge

- Post Office Box

- Potentiometer

- Potential divider

- Ohmmeter

- Resistance thermometer

- Strain gauge

- E-meter - a variation used by Scientology

References

- ^ "The Genesis of the Wheatstone Bridge" by Stig Ekelof discusses Christie's and Wheatstone's contributions, and why the bridge carries Wheatstone's name. Published in "Engineering Science and Education Journal", volume 10, no 1, February 2001, pages 37 - 40.